The rise of civic crowdfunding offers opportunities for local government keen to encourage community initiatives. But is its appeal not confined mainly to a limited, relatively well-educated group? Amsterdam University of Applied Sciences has been investigating.

By Frank Jan de Graaf, Ezrah Bakker – 7 november 2017

Rodrigo Davies, a pioneer in the field of crowdfunding research, says there is an urgent need to gather data about projects in this domain in a structured way. This would provide a clearer picture of the imbalances and power relationships involved.

As far as imbalances are concerned, these are primarily in the distribution of initiatives within a city or region: is it mainly better-educated sections of the community which are taking advantage of these new techniques, and are there differences between urban and rural areas?

The power issue is related to this, but also throws up new questions of its own. For example, are the developments associated with crowdfunding enabling certain interest groups to position themselves better and so benefit disproportionately by attracting more funds and gaining greater influence?

This is the question we have addressed along with our partners, the Dutch civic crowdfunding platforms Voor je Buurt and 1%Club, by combining all available data from their systems about projects undertaken in recent years and subjecting it to an initial analysis. The result is the Civic Crowdfunding Monitor 2017 (http://www.civicmonitor.nl )

Civic Crowdfunding Monitor 2017

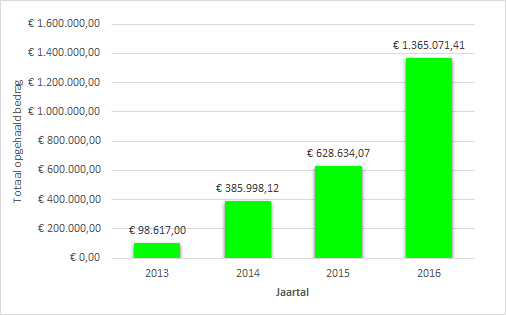

Civic crowdfunding is a relatively new phenomenon in the Netherlands. Since 2013, a number of local authorities have been experimenting with it as a policy instrument. A total of €1.3 million was raised for 260 projects in 2016, from some 20,000 individual donations. More than 90 per cent of this activity was mediated through Voor je Buurt and 1%Club.

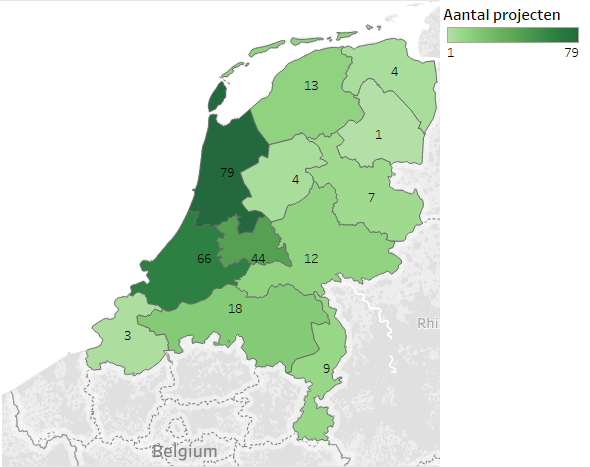

To further analyse the success factors involved, a database was created of all completed civic crowdfunding projects in 2015 and 2016 from 90 percent of the specialist platforms: 475 projects in all, in 36 local-authority areas spread across all twelve Dutch provinces. The resulting resource contains a wealth of information about success rates, donors, themes and additional sources of finance, such as match-funding.

Total amounts raised by civic crowdfunding projects, 2013-2016.

As well as the database, the monitor also incorporates the results of a survey and separate interviews with various interested parties. From these it appears that two broad categories of community initiative give rise to projects backed by civic crowdfunding, each with its own approach to that activity and relationship with the professionals involved.

In the first category, are initiatives set in motion by a small group of relatively well-educated residents in a neighbourhood dominated by middle or higher-income earners. In this case the local authority and the civic crowdfunding professional play a relatively modest supporting role. Those behind the initiative are generally quite familiar with regulatory processes and public administration, and often possess specific expertise in such areas as marketing and social media.

The second category involves neighbourhoods where there are fewer community initiatives because residents tend to lack the networks required. Typically, these neighbourhoods have a high proportion of low-income groups. What initiatives there are usually need manpower as much as they do financial banking, so civic crowdfunding is more likely to be of secondary importance. Residents here have a more traditional view of the role of local government, as a classic service provider and problem-solver.

What makes civic crowdfunding projects successful?

The Civic Crowdfunding Monitor has provided us with a good insight into the factors which make a project of this kind a success. These findings should help the professionals involved to assess the viability of a proposal or initiative.

The rules of the fundraising model used have a major impact upon the project’s chances of succeeding. Specifically, the ‘all-or-nothing’ model leads to a far higher success rate than the ‘keep-whatever-you-raise’ model. With the former, the project only receives the money raised if its crowdfunding appeal achieves at least 80 per cent of its target figure. Moreover, this threshold is imposed as part of comprehensive project policy under which participants are strongly encouraged to attend early planning meetings to take a hard critical look at their objectives before making a final decision to proceed with the initiative.

Initiatives launched by just one or two people are significantly less likely to succeed than those backed by a larger ‘team’.

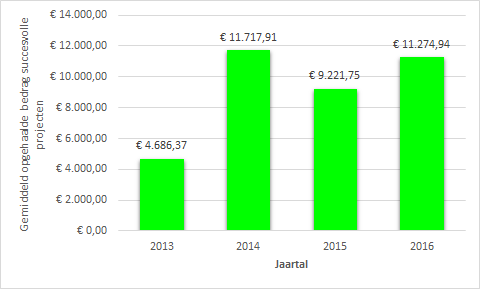

When it comes to amounts, success rates are relatively high at the extreme ends of the spectrum. From this we can deduce that more professionally managed initiatives are good at raising larger sums (€15,000 and over), whilst those run by volunteers have a better chance of success with a modest target (€2500 or less).

Match-funding clearly has a positive effect. This is when a local authority (or sometimes a charity) promises to make an additional contribution if the crowdfunding initiative raises a certain amount.

Average amounts raised by successful projects using the ‘all-or-nothing’ model, 2013-2016.

Scope for greater commercial involvement

In many respects, civic crowdfunding in the Netherlands remains uncharted territory in need of more exploration. Potential initiatives are still sometimes dashed by a lack of skills and know-how. Strengthening opportunities for crowdfunding could remove some of the obstacles to getting projects off the ground.

Also, for a variety of reasons many commercial businesses would like to make a contribution to local initiatives. Some have statutory social-return obligations to fulfill, while others have policies of their own, such as corporate social responsibility (CSR) targets. Ways therefore need to be found to connect these firms effectively to suitable crowdfunding initiatives.

Distribution of civic crowdfunding projects by province, 2016.

Civic crowdfunding for deprived areas as well as the well-educated

From the above, it is clear that civic crowdfunding should not be an isolated activity but part of an integrated approach creating a flexible, ever-changing financing mix, encompassing not only crowdfunding and crowdsourcing but also traditional policy tools such as subsidies and municipal services, as well as business networks engaged in social return and CSR.

The really exciting thing about all this is that, with very different projects in different areas, this approach can help generate an answer to social division tailored to the local situation. In this scenario, civic crowdfunding is not just for the relatively self-reliant sections of the community but can particularly encourage its less capable members as well.

Ezrah Bakker is lecturer-researcher in Business Economics at Amsterdam University of Applied Sciences, and Civic Crowdfunding project leader in the Corporate Governance & Leadership professorship.

Frank Jan de Graaf is Professor of Corporate Governance & Leadership at the Faculty of Business and Economics at Amsterdam University of Applied Sciences.

Literature:

Cullen-Lester, K. L., Maupin, C. K., & Carter, D. R. (2017). Incorporating social networks into leadership development: A conceptual model and evaluation of research and practice. The Leadership Quarterly, 28(1), 130-152.

Centrum voor Budgetmonitoring en Burgerparticipatie (2015). Follow the money. Een zoektocht naar de potentie van budgetmonitoring.

Davies, R. & Roberts, A. (2015). Understanding the Crowd, Following the Community. Working Papers Series Volume 2015, Issue 07. San Francisco: Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco.

Davies, R. (2014). Civic Crowdfunding: Participatory Communities, Entrepeneurs and the Political Economy of Place. MIT Masters Thesis. Cambridge, MA.

De Graaf, F.J., De Jong, G.P. & Zielstra, J. (2016). Vakbekwaamheid en de professional in finance & accounting. Amsterdam: CAREM.

Douw & Koren (2015). Crowdfunding in Nederland, Rapport 2015.

Franke, S., Niemans, J. & Soeterbroek, F. (red.) (2015). Het nieuwe stadmaken. Van gedreven pionieren naar gelijk speelveld. Amsterdam: Trancity*Valiz.

Gerring, J. (2006). Case study research: principles and practices. Cambridge University Press.

Greenwood, D.J. en Levin, M. (2007). Introduction to Action Research. Social Research for Social Change. London: Sage.

Hajer, M. (2011). De energieke samenleving. Op zoek naar een sturingsfilosofie voor een schone economie., Den. Haag: Planbureau voor de Leefomgeving

Hilhorst, P. & Van der Lans, J. (2013). Sociaal doe-het-zelven. De idealen en de politieke praktijk. Amsterdam: AtlasContact.

Majoor, S.J.H. (red.) (2016). Werken in een gebied: gewoon doen in Amsterdam. Amsterdam: ProjectManagement Bureau.

Massolution (2015). Crowdfunding Industry Report.

RMO (2015). Bewust betrokken. De belofte van crowdfunding voor het sociaal domein. Den Haag: RMO.

Stiver, A., Barroca, L., Minocha, S., Richards, M., & Roberts, D. (2015). Civic crowdfunding research: Challenges, opportunities, and future agenda. New Media & Society, 17(2), 249-271.

Tonkens, E. H. (2006). De bal bij de burger: Burgerschap en publieke moraal in een pluriforme, dynamische samenleving. Amsterdam University Press.

Uitermark, J. (2014). Verlangen naar Wikitopia. Oratie Erasmus Universiteit Rotterdam.

Van der Steen, M., Scherpenisse, J., Hajer, M., Van Gerwen, O., & Kruitwagen. S. (2014). Leren door doen. Overheidsparticipatie in een energieke samenleving. Den Haag: PBL/NSOB.

Van Stipdonk, V. (2014). Gewoon doen! Een beschouwing over vier kritieken op de doe-democratie. Bestuurswetenschappen, 68, 70-81.

Voor je Buurt (2015). Slimme subsidie door koppeling crowdfunding.